Very pleased to have met my fellow nominees, the judges and the teams from Amazon and The Walrus! Thank you all!

Boden's "Ashes" shortlisted for first novel award

Many thanks to Barry Coulter at the Cranbrook Daily Townsman for the great article!

You can read more here.

When We Were Ashes shortlisted for the 2025 Amazon Canada First Novel Award

Beyond honoured to be shortlisted for the Amazon Canada First Novel Award! Big congrats to my fellow nominees and much gratitude to my fantastic publishing team at Goose Lane Editions and my brilliant representation at Westwood Creative Artists!

You can read more here….

An Old Story About Metaphysics.

My latest blog post is up at the Human Journey website! I write about how traditional stories and tales can convey valuable lessons about the underpinnings of our world and lives. Enjoy!

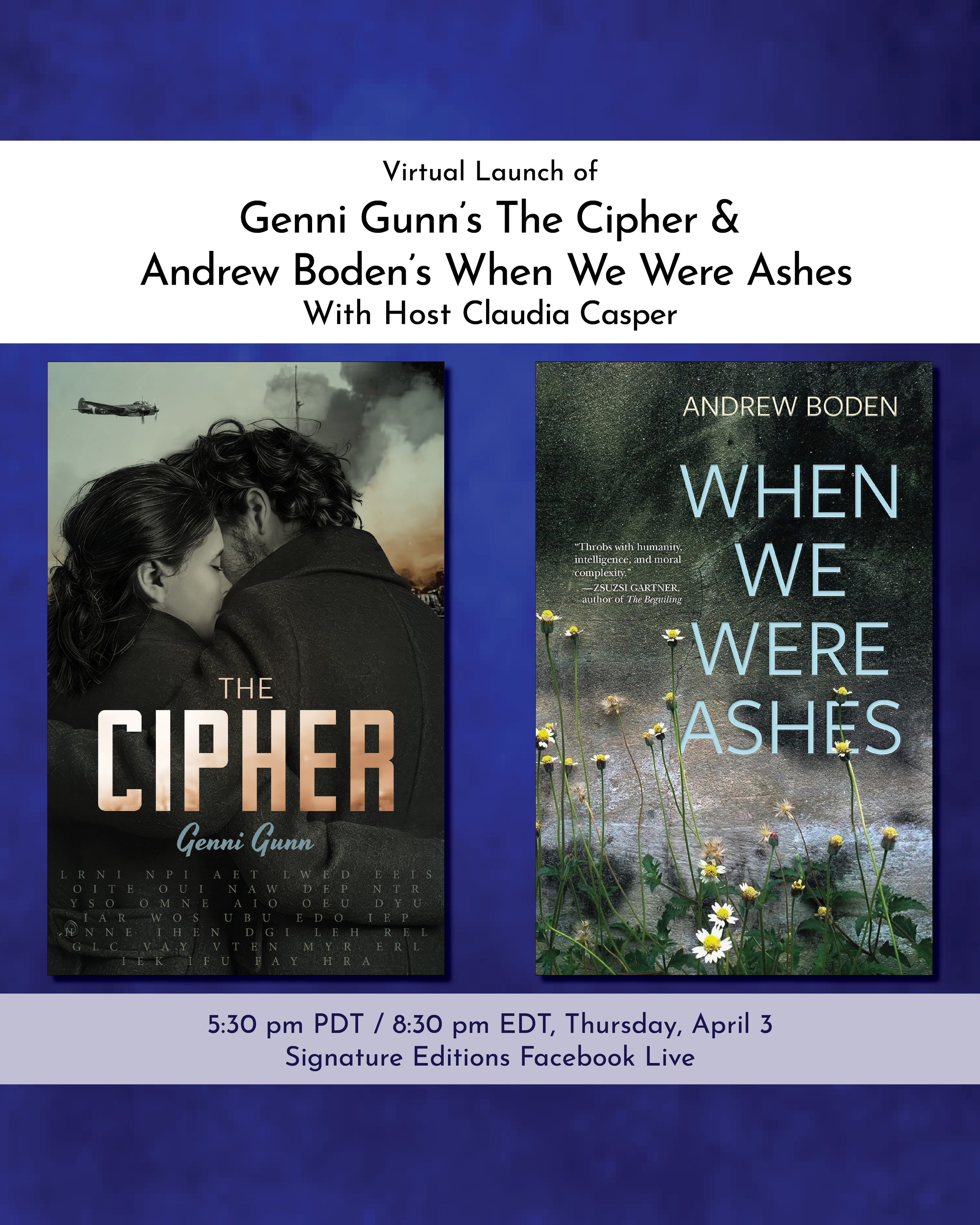

A great online reading event with author Genni Gunn!

If you missed it, you can catch it here on YouTube. Thanks of course for the invite from Genni and Signature Editions! Thanks also to the amazing Claudia Casper for hosting!

You're invited to my joint virtual reading with Genni Gunn!

Come hear Genni Gunn and I speak about our latest work. Genni will be reading from her novel, The Cipher, and I’ll be reading from When We Were Ashes. The event is Thursday, April 3 at 5:30 Pacific time. It’s live on Facebook via the Signature Editions Facebook site. See you there!

Thanks to Everyone Who Came Out to the Book Warehouse!

It was great to do a joint reading with Robert Mackay and have such an engaged, thoughtful audience, too. And thanks again to cellist Anna Kuchkova for her beautiful playing!

Photo of authors Andrew Boden and Robert Mackay.

Photo of cellist Anna Kuchkova and author Andrew Boden.

Reading and Conversations with Andrew Boden and Robert Mackay

Looking forward to seeing you all on Tuesday, March 2, 2025 at 7 p.m. at the Book Warehouse on Main Street! Robert and I are also very pleased to be joined by cellist Anna Kuchkova who will be playing live at the event.

You're invited to "The First Thirty", my interview on Junction Reads

Catch me on Thursday, February 13 at 7 p.m. EST (that’s 4 p.m. PST) for a great reading and live interview about When We Were Ashes, my debut novel published by Goose Lane Editions. This is a live interview via Instagram, so check out @junctionreads and click on their “live” icon in your stories feed at interview time. Hope to see you there!

An invitation to a live Instagram interview with Andrew Boden, author of When We Were Ashes, a novel published by Goose Lane Editions.